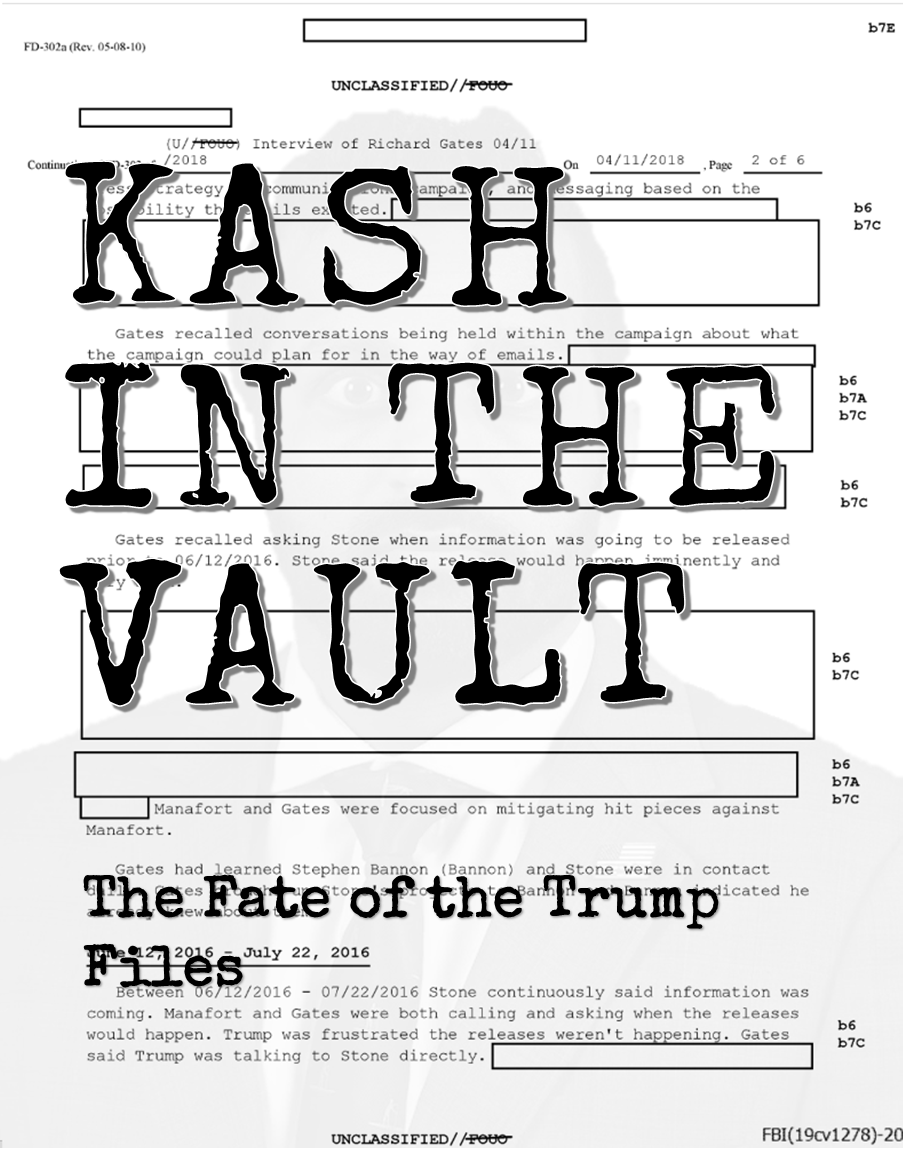

KASH IN THE VAULT

The Fate of the Trump Files and What it Means for Freedom of Information

For decades, federal government agencies have made available the most often requested data under the U.S. Freedom of Information Act on their websites. During the first Trump administration, some of these websites, like the FBI’s Vault, filled up with documents about investigations into Donald Trump, his associates, his 2016 campaign, and his conduct in the years that followed. Reporters successfully wrested these documents from Trump’s FBI via FOIA litigation. The Bureau posted them to the FBI Vault in accordance with FOIA. After Trump’s loss in the 2020 election, the Vault and other government websites also added documents related to the events of January 6th.

This week, Kash Patel, Trump’s nominee for FBI Director, will face a confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee. Patel’s star rose in the Trump orbit as he pushed misleading claims about several of the investigations that the Bureau conducted into Trump.

Now Patel seeks to run the very agency that conducted those investigations, and, if confirmed, will control the FBI Vault, the website that makes the documents in the Trump probes available to the public. The question of what Patel will do with the FBI Vault is a smaller piece of a larger issue—of Trump administration’s clawbacks of previously publicly-available data from FOIA reading rooms and other places on the Internet.

The (b)(7)(D) spoke with several FOIA experts across the country and learned that if Trump officials go after publicly-available information it would merely be a continuation of steps to limit public-access to information undertaken by the first Trump administration. These same experts told The (b)(7)(D) that the results of such a push may succeed. The fate of these Trump files depends on unsettled law and an uncertain public reaction to threats to government transparency.

THE VAULT

The Vault is the FBI’s FOIA reading room. FOIA reading rooms were part of the requirements of the original Freedom of Information Act. These reading rooms were originally physical rooms where the public could see final case decisions, agency policy statements and certain manuals the agency used. These public disclosure requirements were laid out in section (a)(2) of the Act.

In 1996, the Electronic Freedom of Information Act Amendments expanded section (a)(2) requiring agencies to make new classes of information available to the public at large, including any documents that were requested three or more times and any documents that agencies determine “have become or are likely to become the subject of subsequent requests.” In addition to the expanded classes of data, the 1996 amendments to section (a)(2) now required agencies to make the documents available in electronic format. The 1996 Electronic Freedom of Information Act Amendments created the electronic FOIA reading room.

The FBI Vault contains many less-than-flattering documents about President Trump. Not only does it include all 52 document releases from Buzzfeed and CNN’s lawsuit against the DOJ for the records of the Special Counsel Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 election, but also 41 separate releases from the Bureau’s investigation into the events of January 6, 2021.

THE COMMITTED WARRIOR

In his 2023 book Government Gangsters, Patel described himself as a “committed warrior against the corrupt permanent bureaucracy in Washington.” Patel is no fan of the Mueller investigation which he portrayed as “the biggest criminal conspiracy by government officials since Watergate.” Mueller, Patel wrote, was “an utter swamp creature.” The FBI officials who ran the January 6th investigation were, in Patel’s words, “corrupt … the same crew of DOJ officials and FBI agents that ran Russia Gate, the same officials conducting the faux investigation of Hunter Biden.” Now Patel stands on the cusp of directing the FBI, an agency he said “has gravely abused its power” in its investigations of Trump.

TRUMP’S HISTORY OF DOCUMENT TAKEDOWNS

To find out what Patel could do to the publicly available documents from investigations involving Trump, The (b)(7)(D) first spoke with Margaret Kwoka, a law professor at Ohio State University and an expert on section (a)(2) of the Freedom of Information Act. Kwoka told The (b)(7)(D) that a lot of previously publicly available documents were taken down by the first Trump administration. “We’ve seen this before,” said Kwoka, “and not just documents involving Trump.” Kwoka says “she fully expects” to see clawbacks of previously released material in the second Trump administration, citing the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s takedown of data from animal welfare regulators in early 2017, a case that she eventually litigated. The USDA, Kwoka told The (b)(7)(D), cited privacy concerns to justify pulling the data from public view and claimed that the documents would be put back up after redactions.

Professor David Cuillier of the University of Florida concurred with Kwoka’s assessment of the first Trump administration’s record on preserving open data access, pointing to EPA data the Trump administration pulled down shortly after taking office in 2017. Cuillier said there was very little to prevent the second Trump administration from removing publicly available documents from the internet. “Who’s going stop them?” he asked.

Kwoka said that she “can’t imagine we won’t see” clawbacks of previously publicly available documents by the new Trump administration. Professor Cuillier also painted a dire picture of the new administration, telling The (b)(7)(D) that Trump officials were going further than the first term, saying that “wide swaths” of data were being pulled back and that this time Administration officials were “ready for it.”

CAN THE GOVERNMENT LIMIT THE REACH OF FOIA SECTION (a)(2)?

Professor Kwoka told The (b)(7)(D) that the question of whether Patel or any other Trump official could remove documents from an electronic reading room such as the FBI Vault depended, at least in part, on the ability of the public to sue to enforce FOIA section (a)(2) to force the government to restore removed documents to the Internet.

Courts have not settled the question, Kwoka said. The Ninth Circuit, in a case Kwoka litigated, found that citizens did have a right to sue to enforce section (a)(2) of FOIA. In a similar case, the Second Circuit also found that the public could sue. But the D.C. Circuit found that the public did not have a right to use section (a)(2) to compel the government to return documents it had pulled down from the Internet.

The D.C. Circuit is particularly important, because FOIA contains a universal venue clause that allows anyone to sue the government under FOIA to bring a case in Washington, D.C. While the U.S..District Court only handles a small percentage of civil cases nationally, Kwoka told The (b)(7)(D), the court handles approximately 40% of all district court cases involving the Freedom of Information Act.

STAMPING CLASSIFIED ON A DOCUMENT

A related question is whether or not Patel or other Trump administration officials could just reclassify documents in the FBI Vault as classified and withdraw some or all of them.

While Professor Kwoka told The (b)(7)(D) that she can’t think of a time when publicly-released classified documents were clawed back, she said the President could change the executive order that controls classification of documents to create new reasons to classify documents. The presidency’s powers in this area have not the yet been constrained by Congress or the Judiciary. Kwoka told The (b)(7)(D) that she does not know how this will play out.

“SUDDENLY YOU’RE RUSSIA OR CHINA”

Cuillier told The (b)(7)(D) that the question of clawbacks of documents has become critical because the second Trump administration’s takedowns of previously publicly available documents and data “are a lot more broad-based and much faster this term than they were in 2017. We’re definitely seeing a lot more information control so far in this term.”

The larger picture, Cuillier told The (b)(7)(D), is that citizens need to demand the government put more records online. “Democracy is doomed” without transparency, he added, saying that without it, “suddenly, you’re Russia or China.”

Cuillier told The (b)(7)(D) that “there is a ton of evidence” about the effect of transparency laws stating “a transparent government reduces corruption.” But if citizens see less transparency in government, he said, “people start wondering what are they hiding.”